Origins

Lunsingh Scheurleer, a banker from The Hague, is brought down by the 1929 economic crisis and is forced to sell his museum's collection. The Allard Pierson Foundation bought the collection, donating it to the University of Amsterdam, on condition that it would be open to the public. This leads to the establishment of the Allard Pierson Museum on Sarphatistraat on 12 November, 1934. But the history of the Allard Pierson goes back much further, as may be seen below:

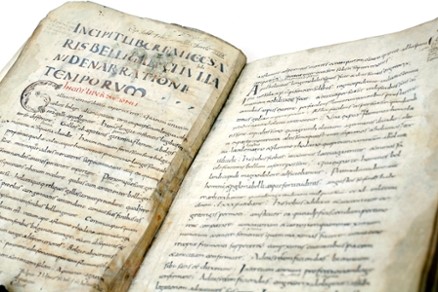

1450 - Monastery libraries in Amsterdam

There were no public libraries in Amsterdam up to the last quarter of the 16th century. The best collections of manuscripts and printed books were to be found in the libraries of the churches and monasteries. There are still sometimes labels denoting ownership as evidence of this. A manuscript on vellum of the Old Testament dating to around 1450, for example, contains the inscription ‘Liber conventus sororum sancte cecylie in amstelredam’: book of the convent of St Cecilia in Amsterdam.

1578 - Founding of the City Library

In 1578, there is a power shift in Amsterdam in favour of reform – or Calvinist – Protestantism. This shift, known as the “Alteration”, means that all church and monastery property fall to the city, including the books and manuscripts. At least some of them are incorporated into the newly established City Library. This book repository was set up in an extension to the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church).

The books in the City Library were kept chained to prevent theft. The folios, bound in calf’s leather over wooden boards with chamois leather backs, lie on lecterns, each in its fixed place.

1599 - Book bequest from Jan Verhee

Donations and bequests from the burghers of Amsterdam gradually extend the City Library assets. One of these benefactors is the alderman Jan Verhee, a man of letters of ‘considerable intelligence’. On his death in 1599, he leaves six books of a classical and theological nature to the City Library. His name is inscribed in gold letters on the covers.

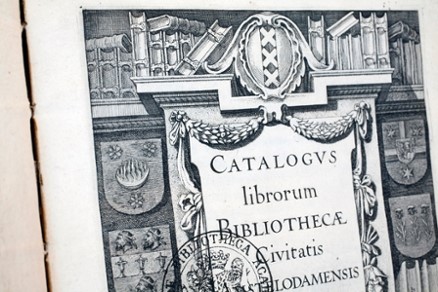

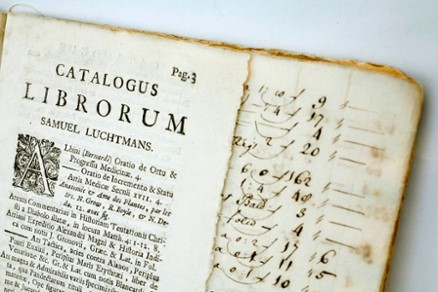

1612 - First library catalogue printed

The City Library’s oldest printed catalogue, compiled by the Englishman Matthew Slade, known as Matthaeus Sladus, is published, not by an Amsterdam printer, but by one in Leiden. The catalogue contains 765 titles, making up altogether around 1,400 volumes. Most of them can still be consulted in the University Library. A second, expanded, edition rolled off the press 10 years later in 1622, put out this time by the Amsterdam printer Paulus Aertsz van Ravesteyn. This edition was decorated with a magnificent frontispiece showing a number of books.

1627 - Donation from the Jacob Buyck library

After the political and religious changing of the guard in Amsterdam in 1578, the pastor of the Oude Kerk takes the community/collection to the Duchy of Cleves on the Dutch-German border. Apart from being a staunch Catholic, Jacob Buyck is a keen bibliophile. On Buyck’s death in 1599, his library returns to Amsterdam to be offered to the city authorities in 1627. This is the first major donation to the new City Library, doubling its collection at a stroke. Most of the more than 1,000 volumes from the van Buyck library are still in the University Library.

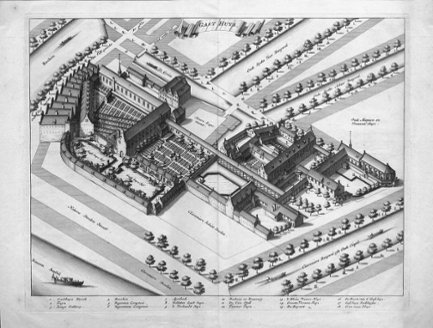

1632 - Athenaeum Library established

The demand for higher education leads Amsterdam to set up a ‘school of inquiry’: the Athenaeum Illustre. The City Library becomes the Athenaeum Library, moving to the attic of the Agnietenkapel (Chapel of the Convent of St Agnes), where the Athenaeum Illustre is housed. The books are chained and can be consulted on lecterns. The imprint of the Amsterdam printer and publisher Lodewijck Spillebout provides a good impression of the situation in the library.

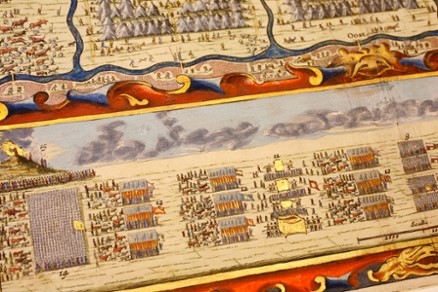

1664 - Joan Blaeu publishes his Grooten atlas (Big Atlas)

Amsterdam publisher Joan Blaeu’s fame is closely tied up with his Atlas maior. which is published in several sections in five languages. Some owners had an ornate display cabinet made for their copy. The University Library has one of these cabinets, containing a Dutch edition of the atlas dating from 1664. Alongside the Grooten atlas, the cabinet contains a city guide in two parts, also published by Blaeu, containing maps of all the cities in North and South Holland.

1695 - Modernisation under Petrus Schaeck

Up to 1695, all the volumes are shown on the shelves with their fore edges facing forwards. The librarian Petrus Schaeck turns the volumes around, adding titles on the chamois leather spines. The chains are also replaced. Schaeck works energetically to enlarge the collection, securing important additions to the library, including a renowned 9th century manuscript of Caesar’s De bello Gallico. This forms the basis for numerous editions.

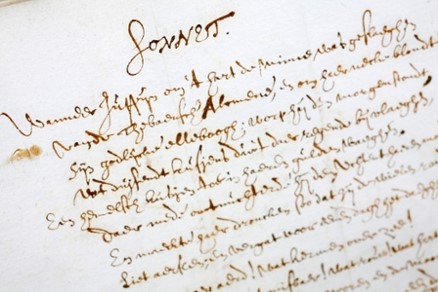

1743 - Donation from Gerardus van Papenbroeck

The numerous sculptures, portraits and manuscripts that the Amsterdam merchant Gerardus van Papenbroeck collects reflect his respect for learning and poetry. He owns the literary archive of Pieter Cornelisz Hooft, which he donates to the Athenaeum Library, along with a large number of portraits. Van Papenbroeck’s example is followed by numerous individuals and institutions over the centuries. Among the major donations are the library of E.J. Potgieter (1875), the Hebraica and Judaica of Leeser Rosenthal (1880), the library of Felix Meritis (1889), the Bilderdijkiana of D.M. de Vries (1891), the collection of autographs of P.A. and W.G.A. Diederichs (1892), the collection of the Nederlandsch Schoolmuseum (1974), the library of the psychiatrist and sexologist C. van Emde Boas (2003) and the Bridgecollectie Amsterdam (Amsterdam Bridge Collection) (2006).

Sonnet by P.C. Hooft

1779 - New directions for the librarian

New directions for the librarian are brought out to prevent theft and damage. Funding is also provided to fill a number of serious gaps in the collection.

By the second half of the 18th century, the library is in a miserable state. Head librarian Jan Hendrik Verheyk notes gloomily that many books are “rotting on their shelves as food for worms and moths”. New directions for the librarian are urgently needed and are issued in 1779. Verheyk successfully argues for targeted book purchases. He also has new bookshelves made, and the chains are removed from the books.

1805 - Use of library subject to rules

There is scarcely any supervision or control of use of the library. The rules of behaviour published in 1805 are aimed at putting a stop to the abuses identified. The head librarian, Hendrik Constantijn Cras, who draws up the rules, sees to it that they are closely observed. Cras had compiled a new catalogue nine years previously, in 1796.

1838 - Move from the Agnietenkapel

The Athenaeum Library leaves the attic of the Agnietenkapel after more than two centuries. The growing collection calls for more spacious accommodation.

Under David Jacob van Lennep as head librarian, the library finds a new location on the spacious and heated upper floor of the Palace of Justice on Prinsengracht. This location is in use until 1863, before the library moves into large premises at Herengracht 40, the former offices of the Netherlands Trading Society (NHM).

1856 - Collection enlarged through loans

Following an excoriating report on the library’s state, the curators appoint the young librarian Pieter Anton Tiele as custos. He implements a new policy aimed at securing loans. The first major loan agreement is concluded with the Koninklijke Nederlandsche Maatschappij tot bevordering van de Geneeskunst (Royal Dutch Society for the Promotion of Medicine – KNMG). Subsequent important loans are made by a wide range of foundations and societiesthe Remonstrantse Gemeente Amsterdam (1878), het Genootschap ter Bevordering van de Natuur-, Genees- en Heelkunde (1880), het Koninklijk Nederlands Aardrijkskundig Genootschap (1880), het Wiskundig Genootschap (1880), de Maatschappij tot Bevordering der Toonkunst (1882), de Vereeniging Het Vondelmuseum (1902), het Nutsseminarium voor Paedagogiek (1925), het Evangelisch Luthers Seminarium (1871), het Multatuli Genootschap (1931), de Stichting Het Réveil-Archief (1931), het Frederik Van Eeden-Genootschap (1935), de Verenigde Doopsgezinde Gemeente Amsterdam (1968) en de Stichting het Begijnhof (1981).

1877 - Elevation to University Library

With the elevation of the Athenaeum Illustre to the city’s university, what started out as a city library now becomes the official library of the University of Amsterdam. Librarian Hendrik Cornelius Rogge is given the task of converting the library into an institution in the service of scientific research and teaching. In 1881, the library moves from the Herengracht to the former Handboogdoelen (archery shooting range) on Singel. A new book repository is constructed behind the building.

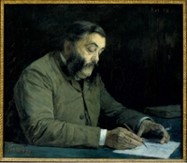

1877 - Allard Pierson

The Allard Pierson Museum’s name derives from the first professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Amsterdam, Allard Pierson. A former priest, he was invited in 1877 to take up the chair of Art History and Modern Literature. Although he established a small collection of plaster casts, this could not be seen as a genuine museum.

Portrait of Allard Pierson, Jan Pieter Veth, 1889, Portraits collection UvA

1890 - Period of professionalisation

The appointment of Combertus Pieter Burger Jr. as librarian marks the start of a period of professionalisation that coincides with the University of Amsterdam’s ‘Second Golden Age’. Under Burger’s stewardship, dozens of specialised catalogues of the special collections, including a series of catalogues of the manuscripts and letters, are published.

1926 – Allard Pierson Foundation

The second professor to teach archaeology at the university, is Jan Six. He owns a large collection of antiquarian books and objects that he uses in his teaching. When he dies in 1926, the Allard Pierson Foundation is established with the aim of retaining these collections for the university. From 1931 onwards, the attic of the Institute for Mediterranean Archaeology on Weesperzijde does service as ‘museum’.

1934 – Allard Pierson Museum

Lunsingh Scheurleer, a banker from The Hague, is brought down by the 1929 economic crisis and is forced to sell his museum’s collection. The Scheurleer Museum had been established in The Hague in 1924 as a private initiative of Constant Willem Lunsingh-Scheurleer. The Allard Pierson Foundation buys the collection, donating it to the University of Amsterdam, on condition that it is open to the public. This leads to the establishment of the Allard Pierson Museum on Sarphatistraat on 12 November, 1934.

Professor Geerto Snijder is appointed the first director of the Allard Pierson Museum in 1934. Snijder collaborates overtly with the German occupation during the Second World War and subsequently serves a prison sentence. Professor Emily Haspels is appointed director after the war. The study collection expands under her leadership with the museum housed on Sarphatistraat, where it serves primarily as a library for students.

The Allard Pierson is accommodated on Sarphatistraat in the 1940s. Housed in an former school building, the basic principle is that a museum should never dominate the artefacts themselves. Rather, museum and display cabinet are there to protect the artefacts. Photo for 1940, Allard Pierson Museum Archive.

De inrichting van het Allard Pierson aan de Sarphatistraat kwam tot stand in de jaren veertig. Gehuisvest in een oud schoolgebouw was het uitgangspunt dat een museuminrichting nooit de voorwerpen mocht overheersen. Wel moesten museum en vitrine de voorwerpen bescherming bieden. Foto voor 1940, Archief Allard Pierson Museum.

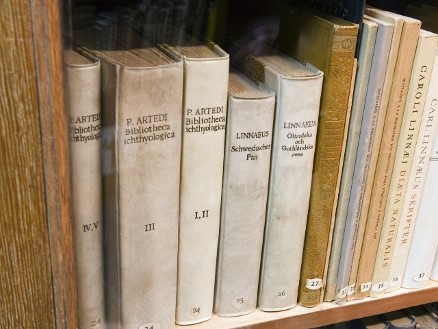

1939 - Artis Library acquisition

The Natura Artis Magistra Zoological Society, established in 1838 to promote the study of natural history, assembles a collection of scientific books and magazines under Gerhardus Frederik Westerman. This library is housed in a building designed for the purpose near the Artis zoo. A century later, the Artis Library is transferred to the City of Amsterdam, which entrusts it to the university. The Artis Library, still housed in the original premises with monument status on Plantage Middenlaan, is currently part of the Special Collections.

All the prints of Linnaeus in the Artis Library

Alle drukken van Linnaeus in de Artis Bibliotheek

1958 - Loan from the library of the Association

Under Herman de la Fontaine Verwey as librarian, one of the most comprehensive and varied collections of historical books in the world is provided with accommodation in the University Library. This is the library of the Vereeniging ter bevordering van de belangen des Boekhandels (Association for Promoting the Book Trade), currently called Bibliotheek van het Boekenvak (Library of the Book Trade). The collection comprises a specialist library on all conceivable aspects of the book trade, along with a large collection of source material on the subject of the history of Dutch books. One of the many collections incorporated is the archive of the Amsterdam Booksellers Guild. This archive holds guild badges, including the badge of the Amsterdam bookseller and publisher Timotheus ten Hoorn from 1681.

1940 - The University Library in time of war

The Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, the University Library’s collection of Judaica and Hebraica, suffers significant losses during the Second World War.

The Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana’s curator and assistant, Louis Hirschel and Meijer Samuel Hillesum, are deported, never to return. The Jewish heritage that was entrusted to their care is withdrawn from use on orders from the occupying forces and removed in part. Library staff secretly hide valuable items from the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana in the Artis Library to secure them against confiscation.

1971 - Acquisition of the Tetterode collection

Thanks to the mediation of Professor Gerrit Willem Ovink, the University Library takes possession of the library and archive material of Lettergieterij en Machinehandel (Type Foundry and Machine Trade), formerly N. Tetterode-Nederland nv in 1971. The comprehensive Tetterode collection is one of the most important collections in the world in the field of graphic technique history. The 19th and 20th centuries are particularly strongly represented. For example, the Tetterode collection includes the working archive of the well-known type designer S.H. de Roos. The so-called “Athias Cabinet” with historical Hebrew type materials (stamps and moulds), donated by Tetterode on permanent loan in 2001, is a showpiece.

1976 – Allard Pierson Museum moves to Oude Turfmarkt

The collection has by now been enriched by a wide range of donations and loans. Important artefacts and collections are acquired in particular under the directorship of Professor J.M. Hemelrijk, making a new building essential.

HRH Princess Beatrix opens the new accommodation in the former building of the Nederlandsche Bank on Oude Turfmarkt in 1976.

2007 - The Special Collections on the Amstel

Twelve kilometres of manuscripts, old and rare printed material, maps, globes, prints and archives are transferred from Singel to the Oude Turfmarkt site, where the Special Collections move into their new home in early 2007. Modern, renovated premises lie concealed behind magnificent historical façades reflected in the waters of a section of the old Amstel, today called the Rokin. They include air-conditioned repositories, reading rooms, reference libraries, an exhibition space and a café. The Special Collections are officially opened by Her Majesty Queen Beatrix on 11 May, 2007.

2019 - A rejuvenated Allard Pierson

In 2019, the Allard Pierson Museum joins forces with the Special Collections under the name Allard Pierson. The museum section of the buildings is thoroughly renovated.